This December our local genealogy society has organized a program on our (in)famous ancestors. One thing I’ve discovered is that some family historians try to hide, apologize for, or otherwise distance themselves from notorious ancestors, while others take a bit of a pride in being able to claim them. I’m definitely in the latter group! So I volunteered a few (yes…I do have “a few”!), and the organizer quickly wanted to know more about Red. I saw the publicity for the event a couple of days ago…looks like Red may be a headliner on the program!

Redmond Boneparte Munkirs — “Red”

This photo is used with permission. It is part of a wonderful online collection known as the Cantey-Myers Collection. It includes many old photos, focused especially on Missouri guerilla fighters and memorabilia

He was born Redmond Boneparte Munkirs in Clay County, Missouri, in 1845. He is my great-uncle through my maternal grandmother, Cecil Munkirs (there’s a chart at the end of the post). Before starting genealogy I had never heard about Red and, in light of our family’s deeply religious roots, I’m not terribly surprised! But his story is fascinating to me and, it seems, to the organizer of the upcoming genealogy society program, as well…so I thought I might share it here while the details are fresh in my mind. Red’s story seems in large part to be an American story which reflects the profound impact of slavery, Civil unrest and war, ongoing national divisions which tore apart families and destroyed lives. His last few years on earth demonstrated the devastating consequences of winning and losing, being on the “wrong side,” and choosing violence to settle disputes and to right wrongs. Such were (and still are) the fruits of bitterness.

Here is the simple announcement of his death which appeared in The Liberty Tribune, Clay County, Missouri, on May 24, 1867.

This is all that was reported in the newspaper about what happened at Red and Mattie Munkirs country home on May 18, 1867. The whole story, however, goes much deeper. — Liberty Tribune, May 24, 1867

Clay County, Missouri, was on the Kansas-Missouri border, to the north of Kansas City. Arguments about The Missouri Compromise, the Kansas-Nebraska Act, and whether Kansas should have been a slave state or free, are things most Americans today know little or nothing about. To the residents of Clay County, Missouri, however such things were very, very important. This was the time, and place, terms like “Jayhawkers”, “Redlegs,” “Free-Staters,” and “Border-Ruffians” entered the vocabulary of American history. And make no mistake, the majority of the residents of Clay County had strong Southern sympathies and alliances. Red was only a teenager when the first shots of the Civil War were heard, but by then his opinions on the issues were certainly well-formed. In 1862 every able-bodied Missouri male was ordered to register for the Federal Army, but Red — along with many other Clay Countians — would not have considered for a moment signing up with the blue coats. The Confederate raiders of Anderson and Quantrill were already becoming active in Missouri, and they were much more aligned with Red and his fellows from Clay County.

We don’t know for sure when Red made the decision to join the Confederate guerilla riders and fighters, but it was at least by 1864. He rode under the command of George Todd, a lieutenant of William Quantrill, so Red was a part of the most feared guerilla band of the Civil War: Quantrill’s Raiders.

We also don’t know exactly when he first met Jesse and Frank James. They were fellow Clay Countians, so he may well have known them before the war. But if not before, surely he met and worked with them during the War as they, too, were Confederate guerilla fighters in Missouri.

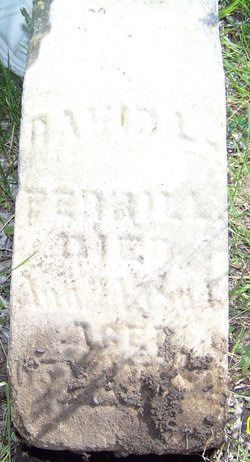

A sad fact of life in Missouri during the Civil War was that no other state saw as many civilian deaths as did Missouri. Some died at the hands of the Confederate guerillas — that is true. But some died at the hands of equally malicious Northern troops and militia. One of those civilians was Judge David Ferrill, of Clay County. Sixty-five year-old Judge Ferrill had never supported the Southern cause (at least openly). He had never taken up arms against the Union and was not known to be a threat to any man. Nonetheless, on August 24, 1864, a Federal militia unit under the command of Captain Richard Sloan rode to the Ferrill home, dragged him from his home, tied his hands behind his back and hung him — in front of his family — from a tree in his own front yard. The family was warned if they cut down the body before 24 hours had passed, they would return to burn down the house. The body of the judge was to be a warning to any who might even consider disloyalty against the Federal army. A small group of neighbors later removed Judge Ferrill’s body and buried him in Shady Grove Cemetery, where his tombstone still stands. Why did the Federal militia do this? Because David Ferrill was the maternal grandfather of guerilla fighter Red Munkirs. Judge David Laird Ferrill is also my 3rd great-grandfather. I can still recall the twist in my own stomach and the flash of indignation when I first read about what had happened to the judge. I can only imagine what Red experienced when he learned about it.

I’ve learned enough about Red Munkirs to understand the last effect that brutal act had on Red was to scare him into submission. Quite to the contrary, in fact.

The Civil War ended not long after, but in western Missouri the feelings did not die down. Many determined to keep alive the spirit of the rebellion and what it represented. Anderson, Quantrill and the other guerilla leaders were either dead or tired of fighting…but many of their followers were not. Among those were Frank and Jesse James, Cole Younger, and others…including Red Munkirs. There are differences of opinion on this, of course, but many historians are convinced the James Brothers and those with them were less interested in becoming outlaws than they were interested in continuing the “struggle against Northern aggression.”

On the afternoon of February 13, 1866, about a dozen men rode into Liberty, Missouri, for the purpose of robbing the Clay County Savings Association. That bank robbery became famous as the first daylight bank robbery in the United States, as well as the first bank robbery of the Jesse James Gang (though it is actually doubtful Jesse was even there that day). But my great-granduncle Red Munkirs definitely was there.

Red died, as we have already seen, at his own residence. He was, in fact, shot to death by a group of unknown riders on May 18, 1867. There’s no evidence any real effort was made to find or prosecute anyone for his death, so it was never solved. His wife, Mattie, was eight months pregnant when Red died. Five weeks later she gave birth to their daughter, whom she named Lorene Redmond Munkirs, after her father.

There’s a LOT more to Red’s story. I’ve been very fortunate to find a nice write-up done by a Missouri historian, Phil Stewart, on Red Munkirs. I have confirmed most all the facts and details. I’ve made a few edits for clarity, added some additional commentary, and corrected a couple of errors. But most of it is not my original work so I can’t take credit for it…Phil Stewart provided most all the material, and I thank him for that.

The Short and Violent Life of Red Munkirs

One more thing you should know about Red…or, at least, the lore about Red. In September, 1866 — about seven months before Red’s murder — there was another murder on a back road of Clay County. Former militia captain, Robert Sloan — the leader of the militia unit responsible for the hanging of Judge Ferrill as well as other acts against the Southern sympathizers of Clay County — was shot dead by an unknown gunman. Three bullets to his chest. It appeared the first shot had knocked him from his horse and killed him. The other two shots appeared to have been added for good measure…perhaps out of spite or revenge. The shooting happened near Shady Grove Church, within eyesight of the grave of Judge Ferrill. The murder was never solved. It was commonly believed the killing was in revenge for Sloan’s wartime acts against the Southerners of Clay County. The man most often cited as the likely shooter was none other than Judge Ferrill’s grandson, Red Munkirs. Red was also buried at Shady Grove Cemetery, though no stone or memorial can be located.